The journey to build an elevator into space

The idea of a space elevator looks like it came out of a sci-fi book by Arthur C. Clarke – and it did. But there are people seriously trying to build an elevator to take us into space: it's a risky plan to create a viable transportation system between the ground and a reference point outside Earth's atmosphere.

The space elevator isn't just a steampunk daydream. If a few tireless advocates of this idea get their way, it will move out of science fiction to be built in the real world.

A futuristic plan (which emerged over 100 years ago)

The idea is futuristic, but it's also quite old: in 1895, Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky drew up an initial proposal for an elevator into space, and this basic concept is still used in projects today.

Over the years, enthusiasm for this project in the space exploration community has been fluctuating – sometimes it rises, sometimes it drops. But now, some high-profile projects are bringing the space elevator back into focus. They have caught the attention of documentarians and dreamers alike, becoming the subject of films like Shoot the Moon and Skyline.

The basic concept, in 1895 and still today, requires an anchored cable stretching into space, capable of transporting people and things out of the world. Tsiolkovsky imagined this cable anchored to the Earth. The details of his design are totally unfeasible: he wanted the weight to be supported from below, while modern planners believe it would have to be supported from above. However, this idea of “a cable from Earth to space” is still the standard concept for space elevators.

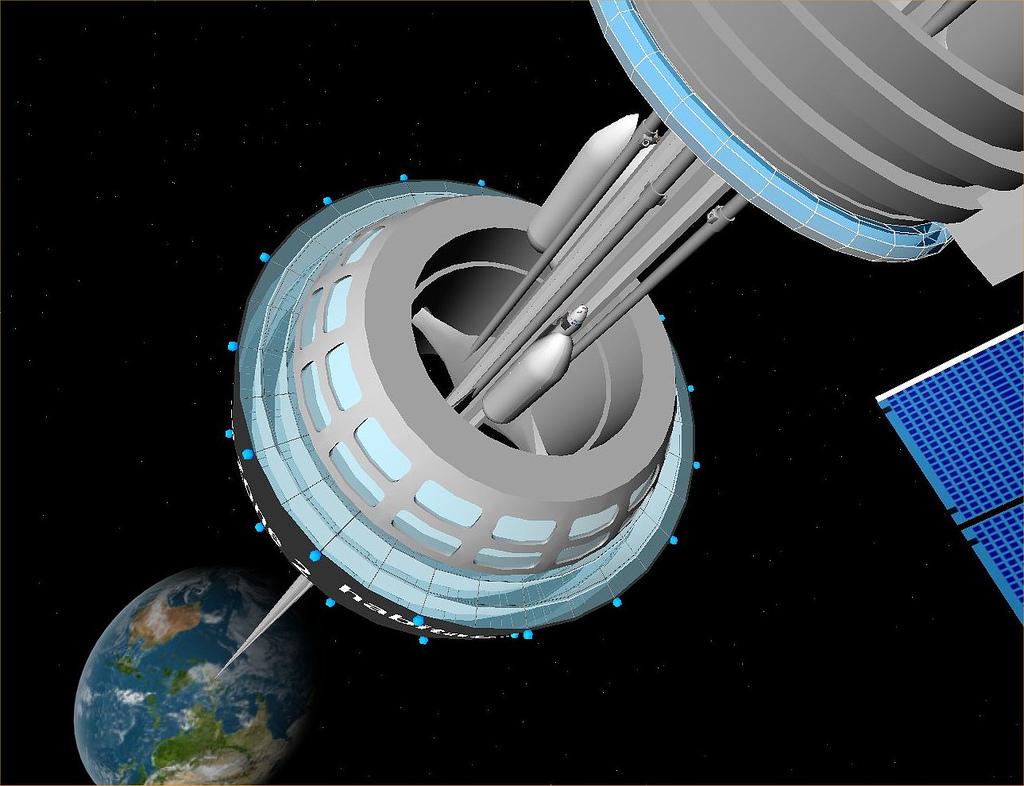

The most accepted plan today involves an anchor point at the equator, with a cable extending some 100,000 km above the Earth's surface, where it would attach to a counterweight station and orbit with the planet.

Concept of a space elevator via Bruce Irving/Flickr

The idea of a space elevator has persisted for more than a century because its advocates see the contraption as a vital step in expanding beyond our planet. It could be, in the future, a low-cost alternative to rockets. Some theorize that because this alternative transport would dramatically reduce the costs of getting people and objects into space, it could democratize space travel.

Today, this is starting to seem more crucial than ever. In a pessimistic scenario, the elevator out of Earth could be a potential escape route: "use it in case of a global apocalypse", a way to start colonizing other planets and preparing for disasters. In a more favorable scenario, space elevators could be a means to enable the expansion of life beyond Earth, and to transport civilization back and forth.

who is trying

But first, we would actually have to build this elevator. And it's not just crazy researchers dedicating themselves to the ambitious project: the Google X lab has recently developed plans to build a space elevator; while they scrapped the project, it's clear the concept is an idea that even Google deems worthy of exploration.

NASA helped hold a competition to encourage space elevator designs. Markus Landgraf, a mission analyst at the European Space Agency, gave a passionate TED Talk about space elevators, saying they would do the equivalent of turning a dirt road into a highway. There is an annual conference on space elevators dedicated to the idea; and this year, a team of experts assembled by the International Academy of Astronauts concluded that space elevators could indeed exist.

In fact, some ambitious projects to transport people into space are in the works.

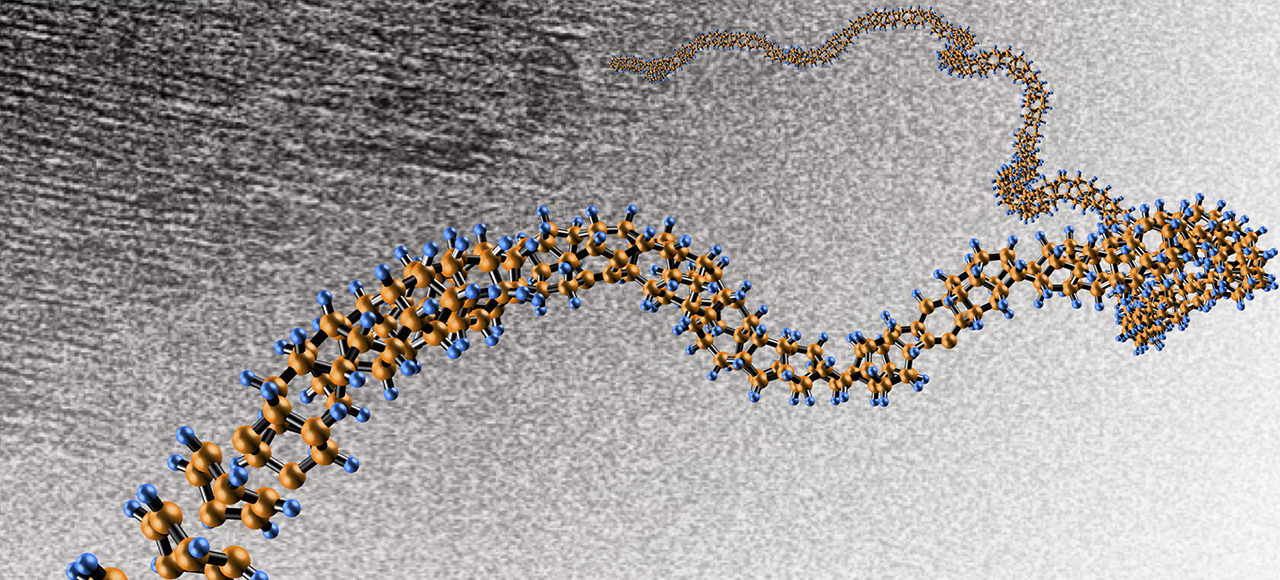

Art by Richard Bizley

Obayashi, a giant Japanese construction company, says it will build a space elevator by 2050, capable of transporting passengers 36,000 km above the Earth, with a "land port" docking in the ocean. It should cost around US$ 8 billion.

The enterprise is grand, but Obayashi is a huge corporation with money and power. There is also the Japan Space Elevator Association working to advance projects like this. It's not something that can be ignored.

LiftPort, founded by former NASA contractor Michael Laine, is a much smaller space elevator operation, but just as bold and potentially valuable. Unlike Obayashi, LiftPort does not have a timeline for building a space elevator. After trying and failing to develop a space elevator in the early 2000s, they started from scratch with a new philosophy.

LiftPort wants to put a space elevator on the Moon. Laine hopes that this lunar elevator will serve as a low-gravity prototype for a space elevator on Earth, as well as an instrument for the Moon to get helium and tour our satellite. The low gravity and zero atmosphere will make it easier to build, even if it's still terribly expensive.

But first, the team is preparing for an experiment that will send a robot to about 7.5 km altitude. If they succeed, this would be the tallest structure in the world – and they would begin plans to build an elevator on the Moon.

It won't be easy: the LiftPort team recently had to redesign their robot, which delayed the project. They couldn't find a test site. They are aware that projects like theirs will be "hellishly expensive". Laine remains optimistic, however:

This robot we're building is an analogy. We are trying to understand the mechanical process of climbing greater distances and in challenging conditions. We can't simulate a lunar elevator very well here on Earth. We are trying to understand the problems. Once we finish this experiment, this will likely be our last one on Earth. We will have practically learned everything we can learn on the planet.

That is, LiftPort is getting ready to build a space elevator getting ready for an experiment, which is going to tell them how to build a lunar elevator, which could tell them how to build a space elevator. This isn't exactly the most straightforward method in the world, but Laine believes this thoroughness will pay off, and his enthusiastic team agrees.

What material?

Skeptics point to several problems with the idea of creating a dizzying high-tech Tower of Babel. While the concept may be logical, the biggest hurdle is that there is no material currently available that is demonstrably strong enough to use in such a structure.

Even if this material is invented soon – and we are getting closer to that – it could also be vulnerable to vibrations. Flocks of birds (at the bottom) and space debris (at the higher parts) could collide with it. Machines for transporting people and cargo could create a lot of sway. Oh, and obviously, it would be terribly expensive to build, preventing it from being realized.

The biggest problem remains this ideal material. Many space elevator proponents – such as physicist Bradley Edwards, who wrote the book The Space Elevator in the 1990s – believe that carbon nanofibers are a strong contender, as they are extremely light and 100 times stronger than steel.

The problem is that no one has ever made a perfect version of a fiber tube that is more than a meter long. That's painfully short: NASA estimates that a space elevator would be 230,000 km. In fact, the lack of available nanofibers is one of the reasons Google X stopped its plans to create a space elevator.

There may be another option: John Badding, a professor of chemistry at Penn State University, believes that tiny diamond nanofilaments hold promise for this task. But even if these nanowires are ideal, that doesn't mean there is a company to manufacture them in the quantities needed for a gigantic cable to space.

Unless these materials become common enough to be manufactured on a large scale, or someone creates space elevators with their own money, even the proper materials may be too scarce and rare to get the idea of a space elevator off the ground.

The real reason to build a space elevator

In addition to all the technical difficulties of actually building a space elevator, there is a legitimate concern that there aren't enough people to create such a machine – few would use it, and it wouldn't make financial sense. Ben Shelaf, a mechanical engineer and former CEO of the Spaceward Foundations - which researches space elevators - developing a lunar elevator is "looking for a solution to a problem that doesn't exist".

A compelling reason to justify this project, and to increase the interest of companies, could accelerate the industrial production of the materials needed to build such an elevator. But Laine says these crazy projects are worth it even if they don't come to fruition.

“The most important reason for doing this has nothing to do with the space, and everything to do with the technology that derives from the construction process,” he told me. “A lot of amazing technology was developed going to the Moon. So here we are, a private company that, for all intents and purposes, is a factory of ideas. We come up with new ideas, and they all focus on the concept of going to the moon, but we can take those ideas and commercialize them… You can make loads of money and make the world a better place.”